How to invest in timber

by George Nichols | June 22, 2008

Introduction

As noted in my previous article, timber has delivered high risk-adjusted returns while serving as an excellent portfolio diversifier and a partial hedge against inflation.

Despite the compelling case for this asset class, the world of timber investments is fraught with peril. I've been disturbed by the misleading statements made by product marketers -- and troubled by the misconceptions perpetuated by media outlets -- regarding this asset class. I hope this article will debunk the myths that are leading investors to make costly mistakes. Before I elaborate, let me review the ways investors access this asset class.

The most direct option is to buy your own forest, which is as impractical as stuffing your basement with oil barrels in order to gain commodities exposure. Instead, what ultra-wealthy individuals and large institutions usually do is invest through timber investment management organizations (TIMOs). TIMOs typically require a minimum investment of several million dollars, putting them beyond the reach of virtually all individual investors, as well as many institutions.

Ordinary investors seeking timber exposure have instead turned to specialized ETFs or real estate investment trusts (REITs), whose pros and cons I'll review.

Timber ETFs: A sector bet disguised as an "asset class"

In November 2007, the Claymore/Clear Global Timber Index ETF (CUT) became the first American timber ETF to hit the market. On June 25, 2008, it was joined by the iShares S&P Global Timber & Forestry Index Fund ETF (WOOD), which had already been trading in Europe (WOOD.L) since October 2007.

Promoters have suggested these ETFs provide smaller investors with an excellent way to access the asset class of timber. Perpetuating such myths, numerous media articles have provided favorable or uncritical portrayals of these vehicles, which have attracted many investors.

But the conventional wisdom is wrong. Timber ETFs actually do not provide investors with direct access to this asset class.

These ETFs are broadly focused on forestry/paper stocks, which lack most of the benefits associated with timber investing. CUT's top holdings include International Paper (IP), a manufacturer that derived only 2.1% of its revenue in 2007 from timberlands. CUT shareholders who think they're diversifying into an attractive asset class are actually making a questionable sector bet.

Timber ETF Correlations

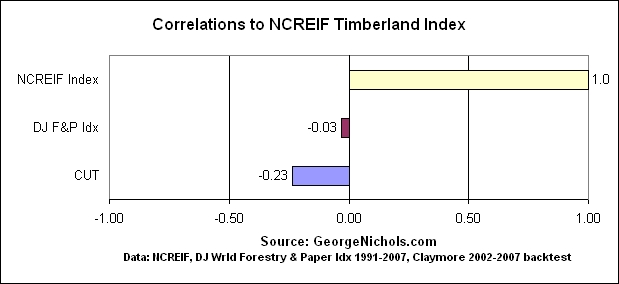

To gauge whether CUT is an effective proxy for timber, I calculated the correlation coefficient of its annual returns (using its backtested results since 2002) relative to an established timber benchmark, the NCREIF Timberland Index.

(As a cautionary note, let me emphasize that the statistics I present throughout this article are historical rather than predictive, and based on a very limited time sample, reflecting what little data is available.)

So, what is a correlation coefficient? In a nutshell, a score of -1.0 indicates one investment has tended to go up while the other asset has gone down, 0.0 indicates the two move independently of each other, and 1.0 indicates both investments tend to move in unison. I'd say a decent timber proxy would score at least 0.80.

My calculation indicates CUT isn't even close to being a timber proxy, registering a -0.23.

However, this calculation is based on a short time period, and I suspect longer-term correlations aren't quite so negative. So, I tested CUT's self-selected benchmark, the Dow Jones World Forestry & Paper Products Index, using available historical returns from Jan. 1991 thru Dec. 2007. The DJ-WFPPI index scored just -0.03, indicating no correlation with timber. Granted, CUT has somewhat less exposure to manufacturing than this benchmark does, but the variance isn't nearly enough to make CUT resemble a timber proxy.

To put these figures into perspective, investors would do a much better job (albeit still a poor one) of tracking timber by buying an S&P 500 index fund. Ultimately, CUT shareholders need to ask themselves why they are making a bet on the paper/forestry products industry.

(click on any graphic to see all graphics in full size)

Comparing the timber ETFs

Timber assets significantly increased in value during the recent stock market downturn, however the market has not been so kind to paper/forestry stocks. Since CUT's launch, the ETF has plunged around 20% (through June 20th) while WOOD has fallen "only" around 10%. So far, WOOD's returns have tracked the S&P 500 somewhat closely, implying low diversification benefits.

Based on my assessment of the ETFs' underlying portfolios, I'd say WOOD boasts somewhat greater timber exposure, which may explain why it suffered a milder decline during the recent market downturn. Most notably, WOOD's exposure to timber REITs (24%) is double that of CUT's (12%). Nonetheless, as with CUT, WOOD's fatal flaw is its heavy exposure to wood manufacturing and distribution businesses. I'd say timberland-related sales account for less than 20% of total revenue among the combined holdings of these timber ETFs. And this exposure is indirect via equities, rather than directly through ownership of trees.

Timber vs Manufacturing

In my view, the costliest error that investors make is lumping together the unrelated industries of timberland management and wood manufacturing. Both markets deal with wood; however, there's a dramatic difference in their underlying economics.

In addition to high labor and energy costs, wood manufacturers are burdened with heavy capital expenditures for equipment and facilities. In fact, academic research suggests the pulp & paper industry may be twice as capital intensive as any other major US industry [1]. All told, mill operators are notorious for poor operating margins, highly cyclical results, capacity problems, depreciating assets, high debt loads, and much higher tax rates compared to what REITs pay for their timber harvests.

By contrast, trees are relatively low-maintenance assets. After all, trees have grown successfully for nearly 400 million years without human assistance. The key ingredients for tree growth -- soil, sunlight, air, and water -- are readily provided by Mother Nature at no cost. Timber may be the only asset in existence that reliably exhibits physical growth for decades with little involvement from the owner. [2]

Nevertheless, there is a widespread misconception that timber and manufacturing assets are comparable. I was disappointed by a recent Barron's article [3] that used an invalid data point to support their assertion that timber REIT Plum Creek was overvalued:

"...Plum Creek shares also trade at 3.8 times book value -- compared with 2.6 for Potlatch and 1.4 for forest-products companies."

In this case, book value isn't meaningful because accounting practices understate the value of timber assets relative to manufacturing assets, as these authors from Hancock Timber Resource Group explain (emphasis added by me) [4]:

US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) consistently understate the returns from timberland -- book values cannot be written up as trees grow; and a noncash cost, "depletion" (similar to depreciation) is deducted from operating EBITDA to compute GAAP net income, despite the fact that the forest asset may be accreting in value [...]

The return to shareholders, whether measured by return on capital employed or return on equity, for integrated forests products companies has been comparatively low (5% to 7%), while returns from timberland have been far higher (as we will see below, the returns from US timberland have averaged 15.3% since 1987). Since integrated forest products companies are nothing more than a collection of timberland and manufacturing assets, the disparity of returns highlights the comparatively poor operating performance of the manufacturing assets.

In an email conversation with me, Daniel Rohr, an equity analyst for Morningstar, agreed with my opinion on book value. Rohr, who covers the paper and forestry industry, added: "In many cases, timberlands were purchased several decades ago, so not only does their book value fail to capture biological growth, but the power of plain ol' compounded inflation as well. I can think of examples where certain parcels are held on the books at $10 or less per acre, when the current market value is well in excess of $1,000." [5]

Timber REITs: How much timber do they really have?

There are three timber REITs: Plum Creek Timber (PCL), Rayonier (RYN), and Potlatch (PCH). Plum Creek stands out from the pack -- it was the first timber firm to become a REIT, and its 8 million acres of American forests makes it the country's largest non-government owner of timberlands.

Unfortunately, none of these REITs are pure-play timber firms. Rather than divest their manufacturing operations, the REITs have merely reorganized them into taxable subsidiaries. Thus, REIT shareholders are stuck with significant exposure to sawmills and paper mills.

This is why it's important for investors to examine corporate SEC filings to figure out what they own. My reading of 10-K filing data indicates Potlatch shareholders have basically owned a manufacturer packaged to them in a "timber REIT" wrapper. As my graph shows, timberland-related sales (which I define as timber harvesting revenue plus real estate gains from the sale of timberlands) made up less than 17% of total revenue in 2007, while the other 83% came from manufacturing. Timber makes up a slightly greater proportion (28%) of revenue for RYN. Plum Creek has, by far, the highest timber exposure (71%), and is the only REIT that I'd have no reservations calling a timber company. (Pope Resources and Deltic Timber, also depicted in the graph, are non-REITs I'll mention later in this article.)

Will Potlatch really become a pureplay REIT?

In April 2008, PCH announced that it was evaluating a potential spin-off of its pulp-based businesses. After those businesses are divested, the residual company will become "essentially a pure-play timber REIT," exclaimed the company's CEO in a press release. Excited investors sent the stock skyrocketing on this news. However, I came away underwhelmed after calculating some numbers for this hypothetical company.

Based on 10-K data, I determined that only 45% of the residual company's revenue in 2007 would've been timber-related. That figure rises to 49.6% if I conservatively subtract revenue (based on my estimates) from a recently closed mill. Thus, the proposed Potlatch is shaping up to be a "half-timber play" (the other half being mills retained in its Wood Products segment). While that figure represents a big boost from its current 17%, it is well short of 100%, or even Plum Creek's 71%.

REITs: Not a pure timber proxy

As a group, the three REITs exhibited fairly low correlations (ranging from .04 to .33) to timber during my sampled period [6]. (Deltic Timber (DEL), a non-REIT firm heavily involved in manufacturing and non-timberland real estate development, showed similar results.) While I anticipated these results for RYN and PCH, I was suprised that PCL -- the sole near-pureplay timber REIT -- exhibited such low correlation.

So, why haven't these REITs shown greater correlations to timber?

Manufacturing operations may be the biggest culprit, as I've already explained. Hypothetically, manufacturing also gives rise to conflicts of interest. Unlike the TIMOs constituting the NCREIF Timberland Index, REITs may be tempted to prematurely harvest timber -- or sell trees at deflated prices -- in order to subsidize their mills.

REITs are also publicly-traded entities that are susceptible to the various economic factors affecting all equities. As a corollary to this point, TIMOs can afford to defer harvesting for years, but REITs may face shareholder pressure to cut trees prematurely in order to meet quarterly dividends or other short-term financial targets.

The REITs are unlikely to resolve this manufacturing-versus-timber tug of war anytime soon. In fact, Congress recently passed legislation (The "TREE Act" of 2008) that, in my opinion, strongly reduces the incentive for REITs or forestry companies (like Weyerhaeuser, which lobbied aggressively for this bill) to ever become pure-play timber REITs.

Also, REITs derive some of their timberland revenue from real estate rather timber harvesting. For instance, while 71% of Plum Creek's sales is timberlands-related, 47% came directly from timber harvesting, while 24% was derived from the land that the trees are sitting on (e.g. selling forests to conservation organizations, or developing forestland for sale to residential property managers).

Lastly, it's worth noting this data is merely a snapshot of the past decade, and I suspect correlations will increase in the future as these firms continue to divest manufacturing assets in order to focus more on timber.

POPE: a timber pure-play but not a timber proxy

More than 97% of Pope Resources' (POPE) revenue is timberlands-related, so it is a pure-play. Pope exhibited a moderately high correlation coefficient of 0.67 during the sampled period. However correlation statistics fail to convey the high volatility of this micro-cap vehicle. During the 11-year span from 1997 to 2007, POPE either gained or lost more than 20% annually seven times, versus zero times for the steady NCREIF index.

POPE is a timber Master Limited Partnership. I'm not a big fan of MLPs, due to their tax complexity, including IRS K-1 forms and unfavorable tax rules for IRA accounts. Investors considering POPE may want to consult a tax advisor.

Wells Timberland REIT

At a glance, the Wells Timberland REIT looks like the real deal: a timber vehicle for small investors. This non-traded REIT, which began raising public funds in May 2007, requires a minimum purchase of only $5,000 and has moderate net income requirements. Another big plus: its portfolio is actually 100% timber-related. As with CUT, several stories from media outlets -- including BusinessWeek, CNBC, and the New York Times -- have mentioned this REIT in stories about timber investing.

However, my examination of its SEC filings uncovered many red flags. For starters, Wells levies huge upfront costs -- up to 10% of the initial investment. There are also onerous redemption constraints -- investors currently can't sell shares unless they die or become disabled.

Shareholders will earn the privilege of selling out -- for an additional cost of 9% -- only after the fund pays down enough debt to meet the financial criteria set by its lenders. That may take a while, given the REIT's dangerously high leverage, as measured by its debt-to-equity ratio. Generally speaking, a ratio of 0.5 or less is considered reasonable, while a ratio above 2.0 is poor. This REIT's ratio of 33 is downright scary.

While the high commissions generated by this REIT make it extraordinarily popular among the financial advisors who sell it, I think it's a terrible deal for investors. You can read more about the dangers of non-traded REITs in this discussion at the Bogleheads Investment Forum .

UK Timber Funds

Those seeking a viable publicly-traded timber fund have to look to the UK, which has multiple timber investment vehicles unavailable to Americans.

Phaunos Timber Fund Limited (PTF.L), which launched in Dec. 2006, is a closed-end investment company trading on the London Stock Exchange. The fund charges investors a management fee of 1.50% and a 20% cut of any returns exceeding 8% annually, plus administrative expenses. Recent performance has been excellent relative to its peers, as illustrated below.

Cambium Global Timberland Limited (TREE.L) is a closed-end investment company trading on the AIM market of the London Stock Exchange. It's still too early to assess the performance of the fund, which launched in March 2007. Cambium manages timber on an environmentally and socially sustainable basis, which should appeal to socially responsible investors, as well as investors seeking returns from carbon credits. The fund charges management fees of 1% and 20% of any returns above 8%, plus administrative expenses.

Like Cambium, the Quadris Environmental Investment Fund manages timber on an environmentally and socially sustainable basis. The fund, which owns fast-growing teak plantations in Panama, does not trade on a public exchange. The minimum investment is 1,000 British pounds. The primary share class has delivered solid results since launching in late 2004, however fees are fairly high. The total expense ratio is 2.16%, which includes an annual management fee of approximately 1.3%. Purchases must be made through a financial advisor, who may charge additional fees. Shares may be sold with a 30-day notice, and there is a small redemption charge if shares are sold within five years.

Huge pent-up demand for timber investment vehicles

While few investors are aware of timber's superior historical performance, those in the know tend to be extremely eager to invest their money.

The three investment products I've panned as being non-timber or financially dangerous have attracted tons of money. As of June 2008, investors have forked over roughly $80 million to the Wells Timberland REIT, while CUT's assets have reached nearly $60 million (as of June 2008). In Europe, WOOD.L's assets are around $12 million (USD), a figure that will increase after its debut in America. It's quite remarkable that these flawed vehicles can raise so much money amidst poor market conditions.

In Europe, Cambium raised over $200 million (USD) for its initial offering. That's impressive, but Phaunos has attracted a comparative tidal wave of assets. Its latest fundraising round will boost total funding to as much as $2.1 billion (!). This includes up to $600 million in an unsolicited offer from a European investment group loosely affiliated with Deutsche Bank.

So, in a span of 1.5 years, this fund has emerged from obscurity and is now on pace to become among the most profitable publicly-traded funds around. Will Phaunos become a victim of its own success? Its asset base may get so bloated that it'll be difficult for the fund manager to find good deals in a market characterized by limited capacity.

Ironically, Cambium's and Phaunos' portfolio managers, as well as some of the funds' holdings, are based in America. This begs the question: Why haven't financial institutions rushed to offer the first bona fide timber fund in America, thereby reaping enormous profits from pent-up investor demand for this asset class? Instead, these providers have been more focused on issuing me-too products, or gimmicky ETFs (like the ones that narrowly track stocks of Wal-Mart suppliers or "gastrointestinal/gender health" companies). Though, in their defense, SEC regulations make it extraordinarily difficult to launch a timber product for the American retail market.

Conclusion

In theory, timber is an attractive asset class that merits consideration for a small slice (such as 5%) of an investor's portfolio. But in practice, a genuine investment vehicle for the masses doesn't exist, and I think investors are better off without timber rather than buying a quasi-timber vehicle.

I think PCL is the most attractive of the available options, even though it's not a proxy for the NCREIF Timberland Index. Nevertheless, PCL reaps many of the benefits of this asset class, is an accessible and transparent large-cap vehicle, and boasts reasonable tax efficiency (unlike most REITs). While micro-cap vehicle POPE is a purer play, it is nonetheless much more volatile than timber is. It also happens to be an MLP, which has tax implications that are confusing and/or adverse for average investors.

In the past decade, several inaccessible asset categories have been made available to ordinary investors, including commodities, inflation-protected bonds, and managed futures. I think something similar will eventually happen for timber. In the meantime, desperate investors will have to move to the UK!

Summary

PCL: closest thing to a pure-play timber REIT

RYN, PCH, DEL: manufacturers with low timber exposure

POPE: timber pureplay, but a volatile micro-cap, and MLP-related tax headaches

CUT, WOOD: unattractive quasi-timber vehicles

Wells Timberland: many problems make it a terrible option

Phaunos: successful timber vehicle in UK

Cambium: new SRI timber vehicle in UK

Quadris: non-traded SRI timber fund in UK, solid record but high fees and illiquid

Footnotes/References

1. Forest Products Journal, "Why forest products companies may need to hold timberland," Sept. 2000

2. Granted, forest managers incur some costs, such as those associated with silviculture (e.g. pesticides), and the cutting/hauling of trees.

3. The Handbook of Inflation Hedging Investments, Chapter 10: "Timberland: The Natural Alternative" (p. 234)

4. Barron's, "Stocks --- The Trader: This 'V' Truly Would Stand for Victory," Feb. 11, 2008

5. E-mail conversation excerpt, June 16, 2008, reprinted with permission.

6. A Merrill Lynch report from May 30, 2008 claims "Shares of Plum Creek demonstrate a strong 0.84 correlation with the NCREIF timberland index" for the 15 years ending Mar 31, 2008. But my calculation for a similar timeframe, 1993-2007, yields 0.37, which is nowhere near 0.84. I wonder what accounts for this discrepancy?

Unrecommended Readings:

Articles that praise -- or may perpetuate misconceptions about -- CUT or Wells Timberland REIT:

TheStreet.com, A New Way to Play Lumber, Nov. 15, 2007

The Motley Fool, An ETF for Tree-Huggers, Nov. 16, 2007

Seeking Alpha, Hedge Your Portfolio With Claymore's New Global Timber Index ETF, Nov. 12, 2007

Seeking Alpha, New Claymore Global Timber ETF Makes the CUT, Nov. 10, 2007

Seeking Alpha, Sowing Profits with the Claymore/Clear Global Timber ETF, May 29, 2008

Hardassetsinvestor.com, CUT-ting Beneath A Timber ETF's Surface, Mar. 27, 2008

ETFzone, Timber ETF Offers Reduced Volatility, Dec. 2, 2007

Blogging Stocks, Cut your volatility with timber, Jan. 21, 2008

IndexUniverse.com, Portfolio Review: Miccolis Watching New Timber ETF, Mar. 2, 2008

Money Morning, Lumber & Paper Mills Struggle as Timber Stands Tall, May 27, 2008

Hardassetsinvestor.com, An Interview with Bruce Zaro, Apr. 28, 2008

Associated Press Newswires, Investors can copy major funds by considering a range of strategies in dealing with ETFs, Jan. 11, 2008

BusinessWeek, Wood Paneling for Your Portfolio, Feb. 7, 2008

* The Timberland Blog: A forestry expert's rebuttal to the BusinessWeek article above provides a rare voice of reason on this topic (even though I don't agree with everything he says).

CNBC TV interview by host Bill Griffith, Timber REIT, May 2, 2007

New York Times, For Some Investors, Money Grows on Trees, May 27, 2007

GlobeSt.com, Wells' Jess Jarratt, May 18, 2007

Investment advisor magazine, "Catching up with...," May 1, 2007

InvestmentNews, Letter to Editor: Article on timber investing overlooked Wells REIT, Mar. 31, 2008